Challenges of developing an automatic bone marrow contouring algorithm: the SPORADIC project

PO-1068

Abstract

Challenges of developing an automatic bone marrow contouring algorithm: the SPORADIC project

Authors: Jose Luis Lopez Guerra1, Pablo Gómez-Millán2, María Perucha3, José-Antonio Pérez-Carrasco4, Begoña Acha5, Carmen Serrano4, Blas David Delgado León1, Oscar Muñoz Muñoz6, Cristina Suárez-Mejías7

1Insitituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla, Universidad de Sevilla-CSIC-Hospital Universitario V. del Rocío, Radiation Oncology , Seville, Spain; 2Virgen del Rocío University Hospital, Radiology, Seville, Spain; 3Virgen del Rocío University Hospital, Medical Physics , Seville, Spain; 4University of Seville, Signal and Communications Theory, Seville, Spain; 5University of Seville, Signal and Communications Theory , Seville, Spain; 6Virgen del Rocío University Hospital, Radiation Oncology , Seville, Spain; 7Virgen Macarena University Hospital, Technological Information and Innovation, Seville, Spain

Show Affiliations

Hide Affiliations

Purpose or Objective

A major health concern for subjects with lung cancer

is the decrease in bone marrow and blood cells during and after thoracic radio(chemo)therapy.

Segmentation is an important and challenging task in the automatic image

analysis of bone marrow. This project addresses the design and preliminary

analysis of an automatic bone marrow contouring algorithm.

Material and Methods

For the development of the automated

algorithm, a technique of statistical methods and Max-flow has been used. This

technique combines gray information and statistical information derived from

combined distance histograms to feed a convex relaxation algorithm for fast and

accurate segmentation of bone structures. Two different segmentation methods

have been carried out that differ in the initial treatment of the image: 1) The

first is based on performing thresholding. The objective of thresholding is to

separate the set of data available in the image into two levels or main values,

so that they are differentiated from the rest of the values present. A value

of 60UH has been used for the threshold, so that all values below this are

discarded, except those that are within pixels of higher values. In this way,

only the bone structures (high UH values) and the bone marrow (pixels included

within the bone contours) are highlighted. To differentiate between bone and

marrow, a new thresholding is performed with a value of 315 UH that separates

the bone marrow and bone pixels below and above said value respectively; 2) The

second method works directly with the available values from the image and

calculates a mean value for bone marrow and bone. Extreme values below 60UH

and above 1500UH are ruled out.

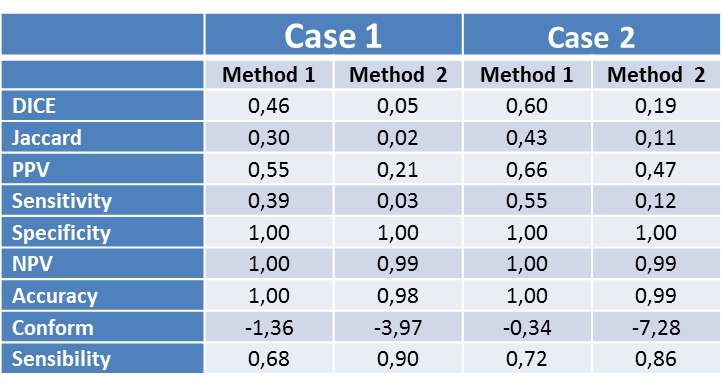

Results

We first segmented manually 2 cases and were

used for training and evaluation purposes. The automated segmentation of the bone

marrow with Method 1 conforms more precisely to the contours made manually than

automated segmentation with Method 2, where the structures marked as bone

marrow exceed the manual contours to a greater extent and are located in areas

in which there is no bone marrow such as the mediastinal region and cartilage sacks.

This is shown in the Table with significantly higher sensitivity

and positive predictive values for Method 1 (0.39 and 0.55 respectively in Case

1; 0.55 and 0.66 for Case 2) compare with Method 2 (0.03 and 0.21 in Case 1; 0.12

and 0.47 in Case 2). The DICE and Jaccard coefficients are also of higher

value, indicative of a greater similarity between the segmentations of the two

cases performed with Method 1 than those performed with Method 2.

Conclusion

The preliminary results of the current work regarding

the development of the automated algorithm for bone marrow segmentation,

although limited, provide a promising starting point from which to develop a

robust segmentation algorithmThe algorithm will help physicians and physicists

in the radiation planning and the analysis of potential constraints associated

with haematological toxicity.